Study by Georgetown Professors, Graduate Students Reveals How Societies Have Survived Climate Change

A team of Georgetown professors and graduate students recently collaborated with researchers in Europe and China on a paper that examines an interdisciplinary field of study they coined the History of Climate and Society (HCS).

The article, which is among the first to be written by environmental historians in the journal Nature, critiques previous scholarship of this field and provides guidance for how our society today can address climate change by studying the past through a new research framework.

“By building on previous scholarship by archaeologists, historians, geographers, linguists, and paleoclimatologists, we found that many societies and communities were resilient in the face of climate change, meaning that they responded in ways that maintained their essential structure, function and identity,” says Degroot. “Our research reveals that many societies effectively responded to the modest climate changes that preceded today’s global warming, suggesting that, with sufficient political will, effective adaptation will be possible for us, too.”

Building a Team

Communities in the Dutch Republic, the precursor state to the present-day Netherlands, were generally resilient to the Little Ice Age. Adam van Breen, “The Vijverberg, The Hague, in Winter, with Prince Maurits and his Retinue in the Foreground,” Rijksmuseum 1618.

The team of 18 researchers, led by environmental historian Dagomar Degroot, came up with the term HCS as a way to describe the field of research that examines the past impacts of climate change on society through different disciplines including archaeology, genetics, geography, history, linguistics and paleoclimatology.

“Until recently, many HCS scholars have worked largely within their own disciplines, without joining forces in interdisciplinary teams,” says Degroot. “We found that a lack of communication between disciplines contributed to biases in HCS research that encouraged scholars to focus on societies that endured crises or even collapsed as climate changed. We draw attention to examples of resilience and adaptation that have too often been systematically ignored.”

To find these examples, Degroot used a Georgetown Environment Initiative (GEI) grant to convene a truly multidisciplinary team of scholars.

The group, first assembled in 2018, includes Kathryn de Luna, Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of history; Timothy Newfield, assistant professor in history and biology; Naresh Neupane, assistant research professor of biology; and Ph.D. students Jakob Burnham (G’23) and Emma Moesswilde (G’24).

A key collaborator was leading tree ring scientist Kevin Anchukaitis (SFS ‘98), a former Georgetown undergraduate student and now an associate professor in the School of Geography and Development at the University of Arizona. Contributing historians included Martin Bauch from the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe, Fred Carnegy from the University College London, Heli Huhtamaa from Heidelberg University, Adam Izdebski from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Katrin Kleemann from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, and Natale Zappia from California State University.

George Hambrect, an anthropologist from the University of College Park Maryland, was also instrumental, as were sociologist Piotr Guzowski from Bialystok University, geographers Jianxin Cui from Shaanxi Normal University and Qing Pei from the University of Hong Kong, and paleoclimatologist Elena Xoplaki from the Justus-Liebig University of Giessen.

Methods and Malleability

With GEI funding, the founding members of the team met at Georgetown to develop a new research framework for HCS scholarship. They eventually drafted a step-by-step process that HCS researchers can follow to more effectively link changes in global climate, local environments, and human societies.

They used this framework to learn how societies endured the largest natural climate changes of the past two millennia: periods of climatic cooling that were caused, in part, by volcanic eruptions. The team found that there were numerous instances in the past where societies were able to adapt to moderate climate change without losing core aspects of their structure.

“We uncovered five characteristics that allowed societies to endure or exploit climate change, including trade networks, governments that learned from mistakes, and the ability to be mobile,” says Degroot. “Our case studies show that human adaptations to modest climate changes were creative and diverse. They also show that during the last two thousand years there was no single, global trajectory of climate’s impacts on human history. Societies did not inevitably collapse or suffer when the climate changed.”

Planning for the Planet

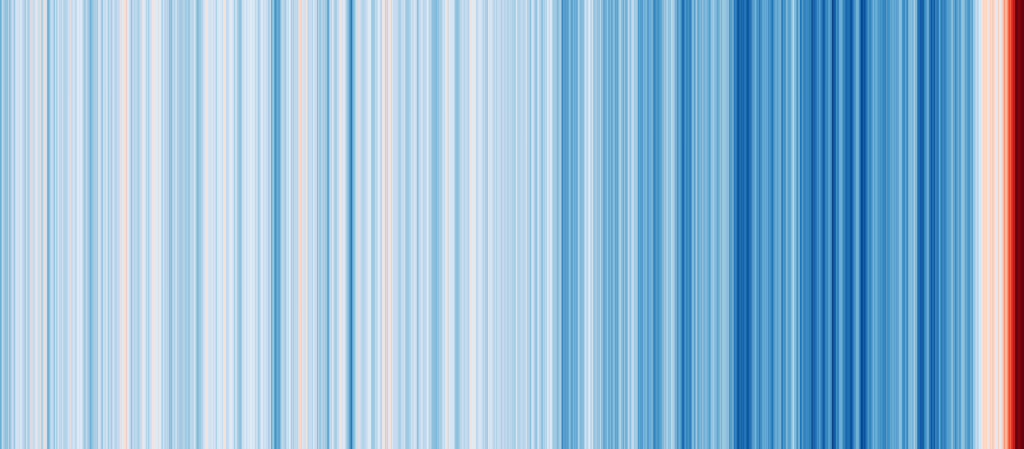

Temperature anomalies in the last 2,019 years. Ed Hawkins using data from PAGES2k and HadCRUT4.6.

While the findings of this research may provide hope for the future of humanity, it is also important to note that these case studies examine instances where societies in the past were forced to adapt to only moderate forms of climatic cooling. Climate models agree that global warming in the twenty-first century will be far more extreme.

Degroot explains that in general, the greater the climate change, the more difficult it is for societies to adjust and maintain resilience.

“While our technological societies may have capacities for adaptation that pre-industrial societies lacked, the warming our greenhouse gas emissions has caused is already much greater in magnitude than the cooling of the Little Ice Ages,” says Degroot. “Our study does not prove that humanity can adapt to the extreme climate changes associated with high or even middle-range emissions scenarios. It is still imperative that we urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions – while adapting to the warming we can’t avoid.”

He also notes due to unequal distributions of wealth in society, some social groups will be more severely impacted than others by climate change – just as they were in the past.

“The capacity for resilience is often – but not inevitably – distributed according to the power, influence and access of unequal social groups. The resilience of one social group – and indeed of one society – may come at the expense of another,” he explains. “ It is urgently necessary for policymakers on every level both to implement effective adaptation programs and to ensure that the benefits are broadly shared.”