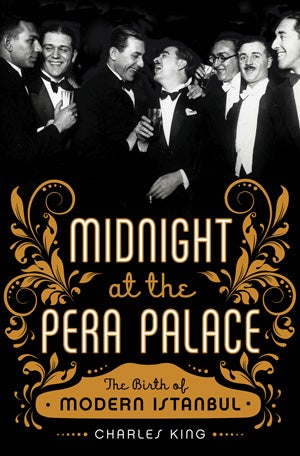

Stories from Istanbul’s Jazz Age

April 7, 2015—Historical accounts of modern Istanbul often focus on the life of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the Republic of Turkey. In Midnight at the Pera Palace: The Birth of Modern Istanbul, Charles King, professor of government and international affairs, paints a different picture—one in which many individuals from different cultures, religions, and backgrounds, must redefine themselves as the world around them changes. “The history of Turkey is far richer and far more complicated, and in so many ways far less rosy and unidirectional, than one might believe,” King says. The College sat down with Professor King to discuss the Pera Palace, its characters, and Istanbul’s Jazz Age.

April 7, 2015—Historical accounts of modern Istanbul often focus on the life of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the Republic of Turkey. In Midnight at the Pera Palace: The Birth of Modern Istanbul, Charles King, professor of government and international affairs, paints a different picture—one in which many individuals from different cultures, religions, and backgrounds, must redefine themselves as the world around them changes. “The history of Turkey is far richer and far more complicated, and in so many ways far less rosy and unidirectional, than one might believe,” King says. The College sat down with Professor King to discuss the Pera Palace, its characters, and Istanbul’s Jazz Age.

Georgetown College: Midnight at the Pera Palace begins as the Ottoman Empire is coming to an end. How did Istanbul begin to change?

Charles King: The book is an investigation of what I call the hidden Islamic Jazz age. This moment in time when this city that had once been a center of the Islamic World—the seat of the caliph of the Ottoman Empire—suddenly became something else. It became not only not the capital of a country any longer but [also] not the capital of an empire any longer. It’s also a moment in time when our conceptions about what “East” is and what “West” is, what “modern” is and what “premodern” is, get thrown up in the air.

GC: And much of that change comes from changes in Istanbul’s population and an influx of refugees from Russia and other parts of Europe?

CK: Many of the refugees in this magnificent city were destitute westerners. Over the course of a few days, 100,000 additional people arrive. It’s this transformative moment in the life of the city and that’s the thing that begins to give rise to jazz and clubs and restaurants and everything that transforms what had been a Muslim space into a very different one.

GC: How was the Pera Palace a center of Istanbul life at this point in time?

CK: The hotel allows you to get into the history of this period. The hotel was the greatest, grandest hotel in the city at the time. It was built in the 1890s. It was the terminal of the Orient Express. It was where if you were taking the Orient Express from Paris you would stay. It was owned by the company that owned the Orient Express.

GC: Who are some of the characters readers meet at the Pera Palace?

CK: There are the famous, the infamous, and the [ones] no one has ever heard of. You have this whole string of very famous people witnessing all of this, [like] Leon Trotsky, who arrives in 1929 and stays for about four years. People like Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos. Agatha Christie comes through.

Then there are some really amazing, fascinating characters that I ended up researching as part of this book. Halide Edip, who was at the time the best-known Turkish feminist who removes her veil in the early 1920s. [She] was just a force of nature in Turkish politics, who’s been kind of written out of that history because she clashed with Mustafa Kemal who becomes Atatürk, the great founder of the Turkish Republic.

GC: Why did you choose to tell the story of Istanbul through the lives of these individuals?

CK: [Scholars] talk in a glib way about big structures changing, empires collapsing, and revolutions taking place. Academics love to speak about structure, big macro shifts in the way the world works. But I think we often forget that structures are conceits of our own scholarly imagination. What really exists are people trying to make sense of a world unfamiliar to them as history changes beneath their feet.

GC: In your writing, you often investigate political science questions through historical narratives; what do you hope readers gain from your books?

CK: I believe the critical thing that historians have to do is enable a sympathetic understanding of the lives of other people. To me history is about the art and science of sympathy. How do you project yourself into a moment in which the categories that people are using don’t make sense, the language doesn’t make sense, the conceptualizations of the world they have don’t make sense? If you can do that, and then get their lives, get why in this time, in this place, people made decisions in a particular way, that is exercising your powers of sympathy in the world at large.

That’s why, to me, history done well is a profoundly moral science. It’s about your ability to get into the life of another person.

—Elizabeth Wilson