Fighting for Justice: Three College Alumni Create Positive Community Change

Three social justice activists who began engaging in community advocacy during their time at Georgetown have continued to fight for others throughout their impressive careers.

Rashawn Davis (C’14), Taylor Griffin (C’14) and Justin Pinn (C’13) found their calling to work in social justice while at Georgetown College. Today, Davis and Pinn serve on civilian complaint review boards in Newark and Miami, while Griffin, who recently stepped down as the press secretary for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, works as a communications manager at Spotify when she is not helping to participate in protests.

Courage to Challenge and Change

Justin Pinn (C’13)

Pinn, who majored in government and English, worked two jobs to support himself and his family while in school. The first-generation college student still managed to be active on campus as a Community Scholar and Georgetown Scholar, and he also served as a student leader in MEChA de Georgetown and secretary of diversity affairs in the Georgetown University Student Association.

“Throughout my time at Georgetown, I constantly questioned whether or not I belonged,” says Pinn. “But I realized that the university also needed me there in order to grow and become a better, more inclusive place.”

He says he also deepened his Catholic faith at Georgetown.

“Our focus on interfaith and being men and women for others was deeply impactful for my development,” he recalls. “It inspired in me the belief that Georgetown uniquely prepares us to not accept the world for the way it stands before us today, but to have the audacity and courage to challenge and change the world for the better.”

Davis, who majored in government, became the co-president of the NAACP chapter at Georgetown.

Griffin, who also majored in government and was active in the NAACP, says the most formative group she joined was the Patrick Healy Fellows (PFH), a community of dynamic leaders who share a passion for addressing issues affecting communities of color.

“The Patrick Healy Fellowship provided me with a supportive family of students and alums who encouraged me to pursue my interest in Congressional politics and helped open the doors on Capitol Hill,” Griffin says. “Just like any other family, they nurtured me, mentored me along the way, checked in on tough days, and celebrated my wins as theirs. And for that, I’m forever grateful for them.”

Pinn grew up in Springfield, Ohio, understanding the importance of civic engagement, service and helping others, but it wasn’t until he worked on the 2008 presidential campaign of then-U.S. Sen. Barack Obama (D-Illinois) that he was inspired to apply to Georgetown.

“I knew that I wanted to go to Georgetown because it would open doors for me to help other people,” Pinn says.

He found his purpose while at the university by mentoring under-resourced students in the DC area. Those experiences opened his eyes to the broader financial and educational inequalities in the country and fueled a desire to find solutions.

A Collective Effort

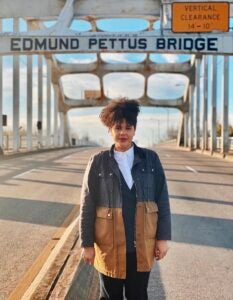

Taylor Griffin (C’14), on the Edmund Pettus Bridge

Following the tradition of cura personalis, Pinn moved to Miami in 2013 to work as a Teach for America Corps member. He taught secondary science to high schoolers, and he now leads Teach for America’s alumni strategy program for the Miami-Dade region.

Pinn became involved in the community and learned of repeated violations, excessive use of force and killings by Miami police against Black men, particularly between 2008 and 2011.

In July 2016, he and 12 other community members were appointed to the City of Miami Community Advisory Board pursuant to a U.S. Department of Justice settlement to provide community oversight and ensure compliance in reforming the Miami Police Department.

“We have collectively worked to ensure each side is listening to the other and that law enforcement sees themselves as guardians within our community,” says Pinn, who has served as the board chairman for the past three-and-a-half years.

Reimagining Policing

He says the recent events surrounding the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others has accelerated conversations.

“We are beginning to collectively reimagine how we conduct and experience law enforcement in our community; the need for more community-oriented policies and investments.”

Davis, a senior campaigner for Change.org, started work similar to Pinn in his hometown of Newark, New Jersey.

The New Jersey native ran for Newark city council during his senior year. Though he lost, Davis noticed the citizens he talked to during door-to-door campaigning asked the same question – What are you going to do about police reform?

“The idea of police reform is not new where I am from, it has lived in the ecosystem of Newark for more than 50 years,” says Davis. “So after I graduated, I joined a team with the ACLU that called for an investigation into the police department.”

The group gathered stories from family members whose brothers, sisters, daughters and sons had been victims of police violence. The results showed a serious lack of police protocol, policy and internal affairs processes.

In response to this investigation, the ACLU created a coalition of community groups across the city to discuss comprehensive police reform.

“We spent many months around tables finding common ground around what police reform could look like,” Davis says. “One thing we always came back to was the creation of a Civilian Complaint Review Board, on which I was asked to serve.”

It Takes a Cultural Shift

Rashawn Davis (C’14) being sworn into the Newark Police Review Board

Davis says positive change has started in Newark, but the progress has been stagnant because of lawsuits filed by police unions against the board’s creation.

“There is a definite cultural shift in the right direction due to the creation of the board, but the majority of the power the board has can’t be fully realized until the court disputes are resolved,” he continues.

In the long term, Davis and Pinn both believe that it is important to reimagine the structure of the criminal justice system and how resources are allocated to communities.

“Right now, you hear people calling to ‘defund the police,’ which I believe is a misnomer,” says Davis. “What they are really calling for is an in depth examination into the ways that we allocate money to the police, and to ensure that this department is scrutinized in the same way every other government department is scrutinized.”

Griffin adds that society often relies on police to serve as mental health experts and to address issues within classrooms, but they are not always properly trained for those services.

“We are putting undue burden on police to respond to these crises,” says Griffin. “It’s really about reallocating resources to places in the community that can more adequately address things like mental health services or care. A staggering number of victims of police brutality are folx who were differently abled or had mental-health concerns within the Black community, and they require a different type of attention.”

Drumbeat Across America

Davis notes that due to social movements fueled by protests, the idea of police review boards and defunding the police have begun gaining popularity across the country.

Griffin has been active in organizing and participating in protests since the police shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and Michael Brown in 2014.

She says that while her job on Capitol Hill enabled her to work to enact policy, she believes participating in protests are the first step towards creating change.

“It is important to exercise our first amendment right to protest because it allows marginalized individuals to be heard when they normally would not,” says Griffin, who lives in Washington, DC. “But protests also cause shifts in public sentiment. When I first started protesting in 2014, the Movement for Black Lives was not a solidified organization. Now it is a drumbeat across America.”

As a result of the 2020 protests that began in response to the deaths of Floyd, Taylor and Ahmaud Aubrey, the House Democrats prioritized addressing policing in the United States.

Prior to leaving her position on the Hill, Griffin was able to witness the House unveil the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

The alumna says the positive outcomes of these protests as well as the important message behind them are what have fueled her and many others to continue marching, despite negative and often violent threats.

“This cause is about my life, about my brothers’ lives, my friends at Georgetown’s lives,” she continues. “And even though I received death threats online or articles that spoke negatively of me from right-wing organizations, I knew that it was a cause worth fighting for.”

- Tagged

- Alumni

- English

- Government