Students Map Out Alternate Futures in Environmental Humanities Course

The dreaded blue book exam has no place in Nathan Hensley’s English 266 classroom. Rather, he asks students to marshall all of their academic and creative faculties to imagine divergent environmental futures by pulling on the vast array of disciplines housed within the humanities. And no, he’s not teaching a capstone course.

Hensley encourages students to pluck at a threat and unravel the knot, seeing how far a topic can take them. Student projects have included an examination of the cost, in both economic and ecological terms, of planting nonnative tulips on the Hilltop every spring and an interdisciplinary interrogation of the salad bar at Leo O’Donovan Dining Hall.

This year was no exception, with students producing podcasts, short documentaries, interactive exhibits and even studio art. For Hensley, that’s part and parcel of the coursework.

“I try to get students to tackle these difficult questions and then identify the most effective medium in which they can convey their answers,” said Hensley, an associate professor in the Department of English. “Sometimes it’s a paper and sometimes it’s not. It enables students to click into something they actually care about and feels real to them and go with it.”

Exploring Environmental Humanities

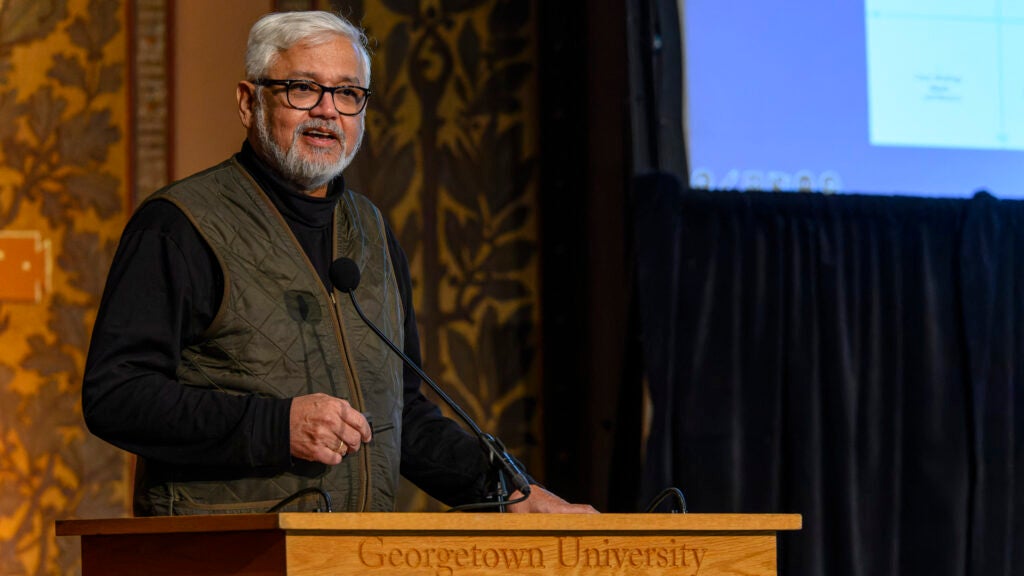

Prof. Nathan Hensley

The course, an introduction to environmental humanities, brings students into a field that, by its very nature, eludes restrictive definitions.

“The question of what the environmental humanities are is open and undefined – there’s not a set curriculum or an anthology that you crack open,” said Hensley. “In this course, it’s about identifying the questions that matter about the environment and the channels of inquiry within the humanities that we can use to tackle those problems.”

Students begin by charting out an environmental and social history of one of the world’s most pressing problems, the climate crisis.

“The idea is to give students a sense of how we’ve arrived at these interlinked failures of climate crisis and biodiversity collapse,” said Hensley. “So we begin with the birth of fossil fuel society and fossil imperialism in 19th-century England.”

Hensley is at home in the writing of Victorian England – his first book, Forms of Empire, examined how 19th-century writers explored the violence of liberal modernity. In this course, students trace the origins of the climate crisis to the invention of land enclosure. They are immersed in Western political theory, introducing students to thinkers such as John Locke and John Stuart Mill.

“When we turn to the present and look at market forces that are interested in commodifying water or turning clean air into a product, we have historical reference points that allow us to categorize these endeavors as new domains of enclosure,” explained Hensley. “It enables us to have a historical perspective on current environmental questions.”

The class examines interlinked Earth systems and processes and examines some places where they’ve failed, like insect die-offs and ocean acidification. The point is to examine how these biophysical crises relate to social and political questions of environmental and racial justice.

“We end by asking how one can imagine futures that don’t match the past,” said Hensley. “I give students the grounding to connect social and environmental histories and then empower students to imagine what kinds of futures might be built from that.”

The Gray Wolf in the Coal Mine

Leyla Hagan (SFS’24)

Leyla Hagan (SFS’24) researched, scripted and recorded a podcast on the American gray wolf. Her three episodes not only examine the animal on its own, but its intersection with American history.

“The incentives of capitalism, folklore and religion had a significant influence on the formation, bounding and growth of not only the United States but the wolf populations within its borders,” said Hagan. “The near extinction of the American gray wolf was encouraged and mandated by the highest levels of government.”

Hagan’s research into the gray wolf’s history not only provides insight into a specific species but how societies interact with the natural world writ large.

“Leyla’s podcast really follows the trajectory of the course, charting the past, present and future of the gray wolf,” said Hensley. “Her multimedia approach shows how complex stories sometimes require new forms of storytelling. I love how ambitious she was, taking that challenge head-on.”

Inspired by her high school interests, Hagan was able to pursue one of her passions as part of the course.

“My research on the American gray wolf actually stems from research I conducted on wolves living at the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem, New York,” said Hagan. “While my career path has taken me away from animals, I still wish to continue my journey of research and advocacy in any way that I can for not only wolf conservation but also the environment more broadly.”

For Hagan, a culture and politics major and math minor, the environmental humanities course enabled her to continue a line of questioning through nontraditional means.

“While it was a lot more reading than I initially bargained for,” laughs Hagan, “I learned a lot about how the discursive processes of the environment and climate change have developed over time. As an environmentalist, it provided me with new frameworks through which to critique the movement over time.”

The Pages Keep the Record

Beatrice Trad (N’25)

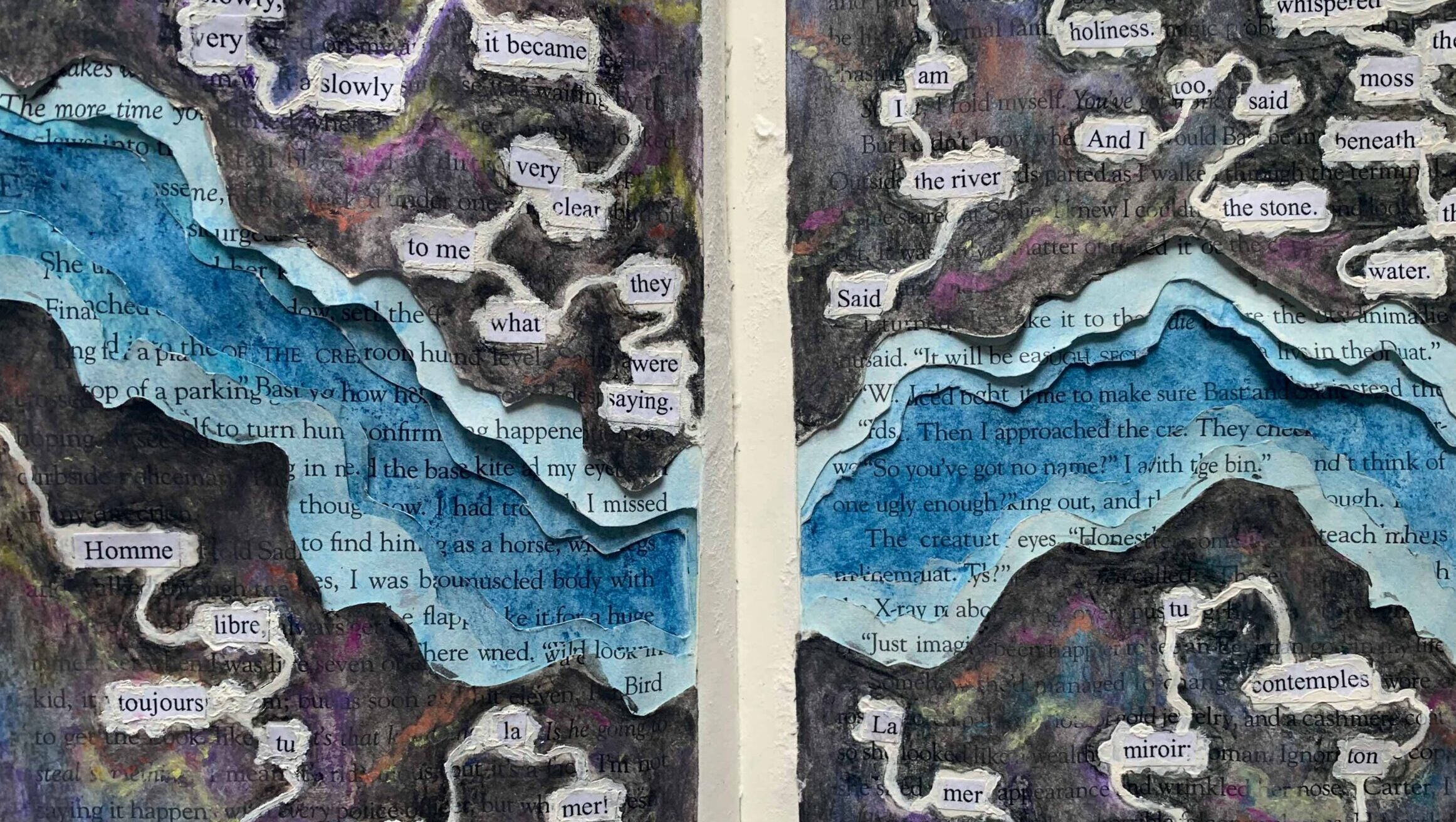

Beatrice Trad (N’25) crafted a multimedia sculpture for her final project – pasting, painting and transforming a novel about myths into a hybrid project titled The Altered Earth.

“An altered book project felt perfect to bring to life the consequences of humanity’s destruction of the Earth,” said Trad, a global health major. “A book itself is symbolic: millions of trees suffer the casualties that give rise to our paper. Thus, my project attempts to display an Earth altered by humanity’s greed through that medium.”

For Hensley, Trad’s project captures what the class is all about.

“Among so many really astonishing projects, the one that made my jaw drop was Beatrice Trad’s multimedia sculpture,” said Hensley. “She’s taken text from the book and transformed it into these poems from poets like Mary Oliver and Emily Dickinson that are about loss and deforestation and the existential condition of the changed world.”

Trad’s piece, Spills Kill, brings together the inherent beauty and destruction of an oil spill.

“When rain falls on asphalt and oil is present, thin-film interference gives rise to a beautiful rainbow of colors, with striking blues, purples and yellows,’ said Trad. “I’ve always thought it curious how such a beautiful process, nearly identical to how a rainbow forms after rain, could actually be indicative of a substance like oil, one of the worst offenders of the climate crisis.”

Alongside the physical work, Trad submitted a paper explaining the medium, her choice of poetry and the resonance it created. The work was invigorating.

“As a student who tends to be on the quieter side, I felt that being in Professor Hensley’s class really helped everyone—even the shyest students—to participate and share analyses as well as personal experiences,” said Trad. “He always welcomed creativity and pushed us to think more critically. I hope to take another one of his classes before I graduate!”

Spills Kill evokes the destructive nature of oil spills through carving into the physical pages.

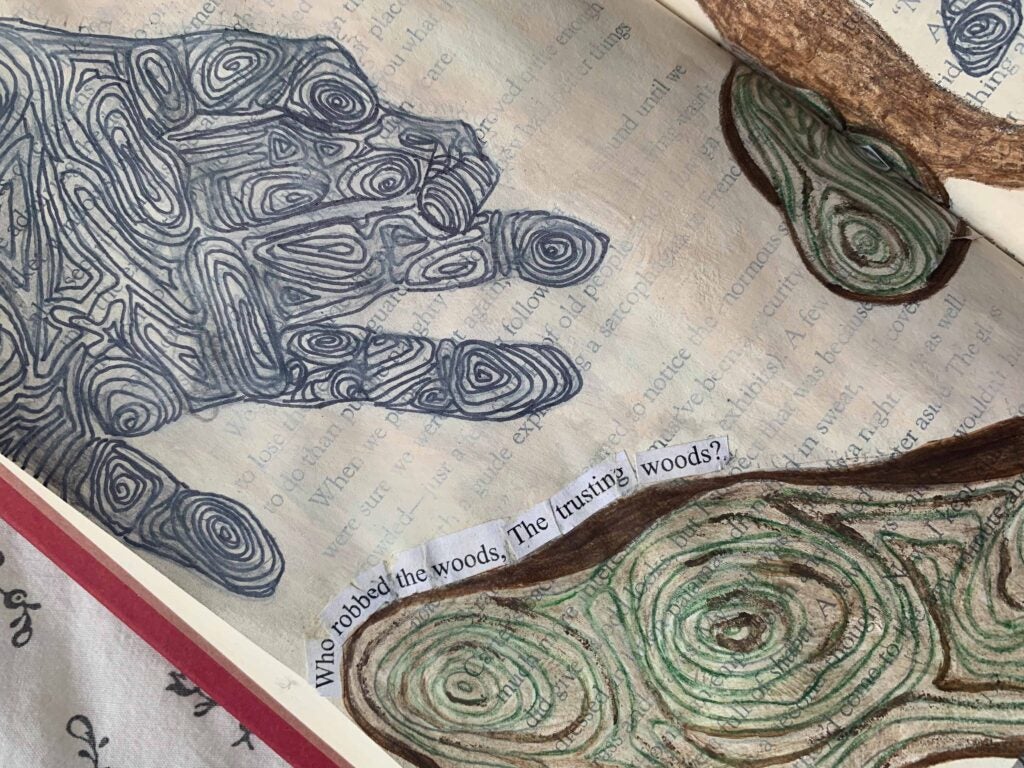

Lifelines brings together fingerprints and tree rings, both symbolic of age and identity. Trad uses excerpts from poetry by Syliva Plath and Emily Dickisnon.

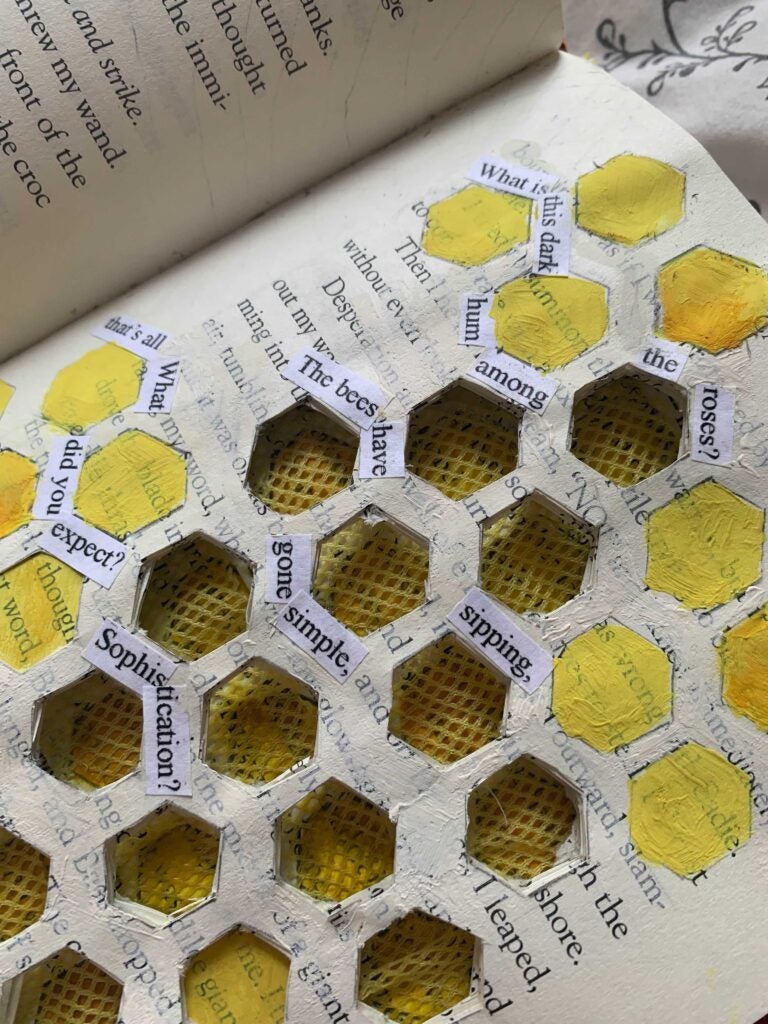

The Birds and the Bees compares the pattern of honeycombs and plastic nets, with birds caught in between.

Consider the Banana

Teagan Quinlan (C’26)

Teagan Quinlan (C’26) scripted, directed and edited a documentary film about banana colonialism and the United Fruit Company for her final project.

Quinlan’s documentary built upon Rob Nixon’s notion of slow violence, wherein violence is perpetuated on such a large timeline that it ceases to be a discrete event and can be exceedingly difficult to pin down and define. In her film, Quinlan explores the relationship between the U.S. military, the United Fruit Company and the subjugation of Latin American populations to produce cheap, widely-available fruit.

“In this course, we talked a lot about how different mediums can impact what information we absorb and how traditional styles of literature are unable to easily communicate the gravity of climate change,” said Quinlan. “I thought that a mini-documentary would better communicate the history of United Fruit than a paper, enabling me to tell a narrative story with archival images.”

Hensley brought the class to Amitav Ghosh’s lecture on The Nutmeg’s Curse, his most recent book that parallels the ecological, sociological and environmental storytelling centered in the course.

“This was unlike any other course that I have taken at Georgetown as it challenged me to see the flaws and limits of literature and how we communicate,” said Quinlan. “Professor Hensley’s teaching style made it easy to comprehend the shift in thinking that was required in order to see society’s anthropocentric tendencies and the problems with modern literature.”

But for Hensley and his students, the limitations are only the beginning.

“We try to see, together, how constraints on what can be said and thought can also open up new possibilities,” said Hensley. “Those are the spaces we try to find.”

by Hayden Frye (C’17)