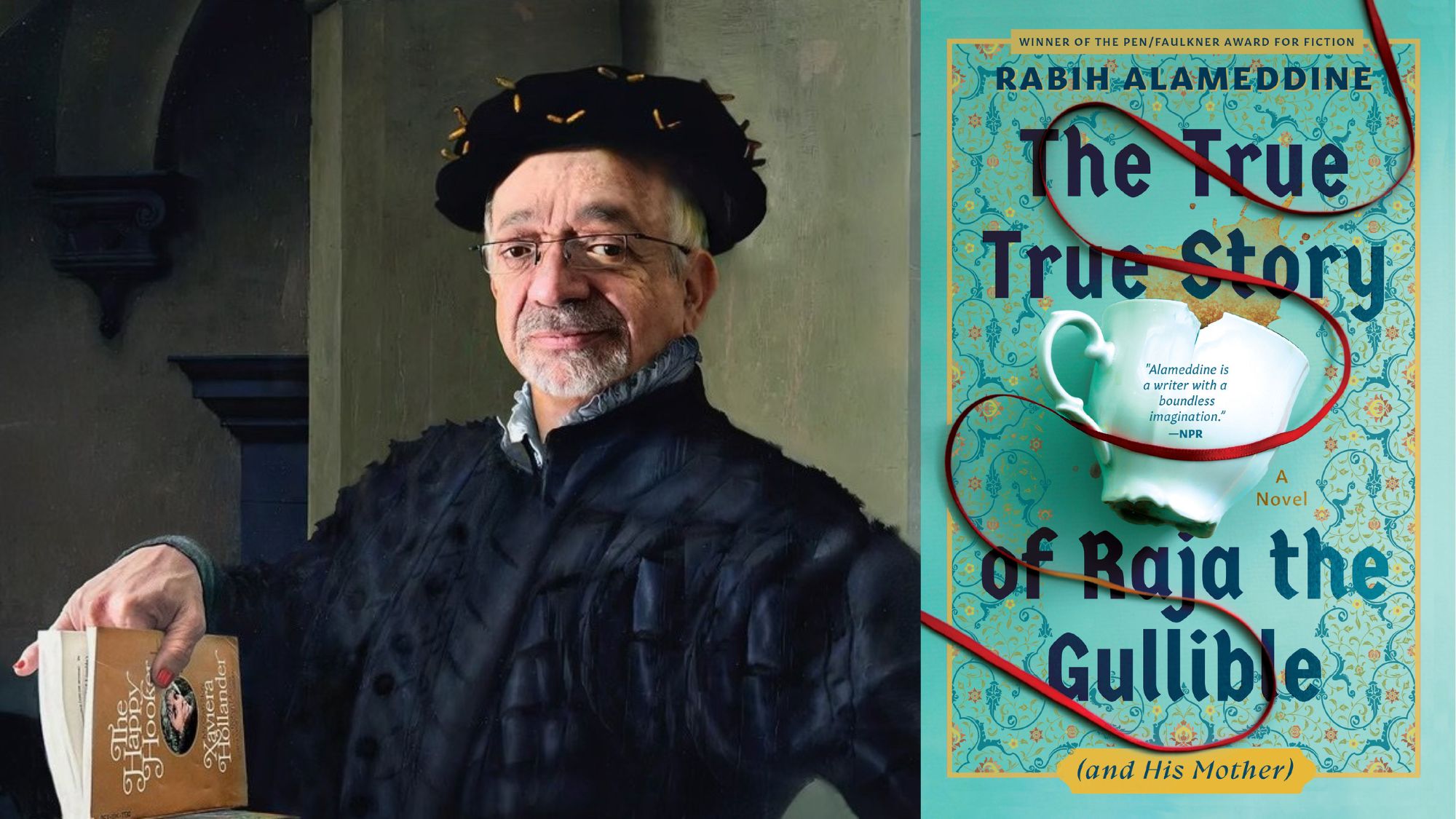

Georgetown Visiting Professor Rabih Alameddine Wins National Book Award in Fiction

Rabih Alameddine, a Georgetown University visiting professor and the Lannan Foundation Visiting Chair, received the prestigious National Book Award for Fiction this November for his novel, The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother).

Alameddine joined the Department of English’s Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice in 2023 and was previously the Lannan Medical Humanities Scholar-In-Residence in spring of 2023. He won the Lannan Prize for Fiction in 2021.

The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) is about the 63-year-old Raja and his mother, Zalfa, who live together in a tiny Beirut apartment. Told through the voice of Raja, the book traces the stories of Raja and of his home in Lebanon across six decades.

Alameddine has authored seven novels, one short story collection and one non-fiction book. The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) is his most recent novel and was published in September. His 2014 novel, An Unnecessary Woman, was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. Alameddine has also received the 2019 Dos Passos Prize, the 2025 Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Publishing Triangle and the 2022 Pen/Faulkner Award for fiction.

The College of Arts & Sciences talked to Alameddine shortly after he received the National Book Award for Fiction on Nov. 19 in a New York City ceremony. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You didn’t study writing at university. How did writing become part of your life?

Reading has always been a part of my life. I’ve been reading as long as I can remember. Before he died, my father reminded me that when I was four, he asked what I wanted to do, and I said, “I want to become a writer.” When I was four, my idea of writing was writing Superman comics and Batman comics, because that’s what I read. So it was always that I read a lot, but I didn’t start writing ’till relatively late in life.

Reading has always been a part of my life. I’ve been reading as long as I can remember.

Rabih Alameddine, author of The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother)

I started writing because I didn’t like what I was reading. The first book was about the AIDS crisis and the Lebanese civil war. We were in the midst of the AIDS crisis, and I did not like how it was being represented, so I sat down and wrote what I saw, and that book [Koolaids: The Art of War] got published.

Have your motivations for writing changed over time?

I always think I write for revenge, which is a very good thing to do. There was an interview with me in a magazine, maybe four or five years ago, and they put one thing that I said on Instagram or Facebook or something. And I don’t hang out that much there, but somebody pointed it out to me, and it said that I still write because I want all the kids who didn’t invite me to their parties in kindergarten to go, “Oh, my God, we should have invited him to that.” I want everybody to regret not being my boyfriend. I want everybody to regret not inviting me to the great parties. And I hate parties, but I want to be invited.

So that’s always the joke in the back of my head, it’s revenge. But primarily I still write because I want to see the books I don’t see, which is a good thing, because nobody else can do it but me. I don’t see the books that I think should be out there, so I write them. It doesn’t mean that they’re better or anything. It’s just a different kind of book.

A lot of people have mentioned the unique voice of Raja. How did his voice develop?

That’s a difficult question, because it’s important to realize that I don’t believe you develop a voice. It’s there. You just unearth it. A lot of writing classes will tell you, “Find your voice.” And I consider that bull—-. Your voice is always there. You’ve never lost it.

I don’t believe you develop a voice. It’s there. You just unearth it … Your voice is always there. You’ve never lost it.

Rabih Alameddine, Lannan Foundation Visiting Chair

The lovely thing about Raja and why I like it is because, in certain segments of the novel, Raja is just sitting and telling a story. And if the story is good, it tells itself. There are things that I did that take it beyond that. But this interview is not a discussion on how you structure it. The second section, that’s pure storytelling. Somebody sitting on a comfortable sofa and telling the story, saying, “And let me tell you what happened here, and let me tell you what happened there.” So that’s sort of the voice.

So, if you want to say the voice is what matters, the voice is just somebody telling a story, somebody with a sense of humor. And, you know, again, for me, what makes Raja charming is that he has a sense of humor. And it’s his self deprecating kind of humor. He makes fun of himself, he makes fun of his mother. He makes fun of everything.

Could you talk about Raja’s relationship with the city of Beirut?

Beirut is important. But every novel, if it’s any good, the setting is important. His relationship to the city is the same sort of relationship that one has with something that is capricious. It offers great solace, and at the same time, it can offer destruction. And so that when you have a capricious God or a capricious city, the relationship becomes in some ways unstable.

I think part of the problem with this country is that everything seems to be predictable, that we forget that life is not predictable. In Beirut, you don’t know if the electricity is going to come on or never come on. You go out, you don’t know if the traffic light is going to work or not. Whereas when you live, say, in Germany or in parts of the United States, where everything is predictable, then you forget that sometimes you get a monsoon, sometimes you get an earthquake. We don’t seem to be prepared for the randomness of life.

What has your experience been of writing about the unexpected in a culture that prioritizes writing about the everyday, the mundane, the predictable?

I’ve always felt like an outsider, whether I was writing or not. My writing has always felt like outsider writing. That does not mean that I was not respected or appreciated, but for the most part, I don’t really represent the dominant culture. Particularly when I first started, my first book was relatively shocking. It took a long time for other people to come in, and other writers, to begin to see the world the way that I do. But that’s normal. If you are to start writing, you will write what you see.

I’ve always felt like an outsider, whether I was writing or not. My writing has always felt like outsider writing.

Rabih Alameddine

What’s important to know, I came from a background where I grew up in a civil war. Then I went through the AIDS epidemic, where I lost so many friends. I started a gay soccer team, half of them died within three years. Half of them, we’re talking like 40. So there were 20 people who died. So I know that I cannot rely on anything, and still I do. It comforts me to know that when I press this button, the computer comes on.

So I started believing that, you know, everything will turn out the way I expect it to. But there’s a part of me that knows, and this is what I write about, that knows that, no, this is not it. So it has to do with how one grows up. When I get too comfortable, I start getting depressed without knowing why. Usually it’s because I’m in my head, and I’m at home all the time. So I start thinking, “Oh, my troubles are like the biggest thing.” But it’s important I put myself in situations where I remind myself that life is not predictable. It’s not always calm and collected.

In the book, there’s a lot of tragedy. What is the role of art in times of tragedy?

Let’s just say, this is a question that cannot be answered. There are many, many roles for art. One of them is entertainment, distraction. The other is being a witness, just recording and witnessing what is happening. And there are some that will tell you that it’s about inspiring. Literature, books have many, many purposes, and different readers use it for different things.

What is the purpose of literature? We’ve been arguing that for generations. It’s like, was Shakespeare trying to create art, or was he just trying to entertain and make a living? And did his work inspire people to do something that they weren’t? It’s a long question.

Usually, when I’m sitting down to write, it’s about making a sentence work. It’s about moving from one thing to the next and finally, getting a book. I don’t think in terms of, I am writing to do this or that. Once a book is done, once a play is written, once a movie is done, what happens is between the reader and the book. I don’t know what the purpose of writing is.

In a quote commonly attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt, she said the purpose of life is to live it. So you can say the purpose of art is to make it. The purpose of literature is to write it. Everything else is secondary.

(Photo of Rabih Alameddine by Oliver Wasow)