An Interdisciplinary Approach to Life’s Big Questions

Uncertainty is inherent to the human experience, but it’s often at odds with planning for the future, living in the moment and making sense of life. To address the issue of uncertainty in existence, the Georgetown Humanities Initiative brought together an interdisciplinary panel of world-renowned experts.

Moderated by Oleg Svet, Ph.D., an adjunct professor in the Center for Security Studies, the event asked scholars from the fields of psychology, physics and art to leverage their unique perspectives and engage in a collaborative dialogue.

“The biggest issues that society faces today, from COVID and climate change to wars and migration, are stark reminders of the uncertainty that shapes our condition,” says Nicoletta Pireddu, Ph.D., the Inaugural Director of the Georgetown Humanities Initiative. “We move in uncharted territories. How do we deal with the unknown, the unpredictable, the undecidable?”

“Our event aimed at offering a comprehensive, humanistic framework to address this deeply human question at the intersection of science and imagination, of the quantifiable and the creative,” Pireddu says.

Ambiguity, Hidden and Present

Daniel Kahneman, Ph.D., a professor emeritus at Princeton, won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his decades of research in psychology. By studying the mechanisms by which humans make irrational, often flawed decisions, he changed how economists view humans as rational actors.

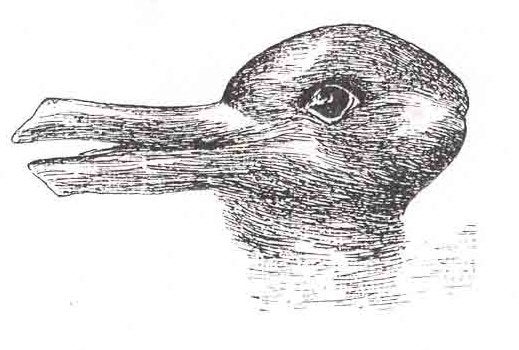

When people are confronted with ambiguity, according to Kahneman, they often make up their minds before they even realize the uncertainty of the facts before them. Ambiguous images, which are drawn to look like two things, aren’t seen as both things at once, but as one or the other. The viewer either sees a rabbit or a bird, but not both at the same time. This kind of perceptual decision making often occurs without a person realizing there is any ambiguity, and is likely an evolutionary byproduct, where we think, decide and act quickly.

Beyond the visual, humans are prone to jump to conclusions when presented with very little information. Most interviewers assume more about job candidates than they know, often based on tidbits of information with little-to-no context.

“Jumping to conclusions is an essential feature of the way our mind works,” Kahneman explains. “And we have a very strong urge to confirm early impressions. Once you have an impression, you’re looking for new information, which you’re going to interpret in a way that is consistent with your first impression.”

Uncertainty isn’t always easily hidden, according to Alan Lightman, a novelist, essayist, physicist and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Uncertainty is a foundational component of the natural world.

Lightman cites Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle as an entry point for understanding ambiguity in the natural world. The uncertainty principle states that an observer cannot know both the position and the speed of a particle with complete accuracy. As more information is gathered on one measurement, less is known about the other.

“Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is not a statement about the precision of the tools we use to measure nature,” Lightman explained. “The principle is a statement about the fundamental nature of the world.”

Much of human progress, according to Lightman, is attributed to eking order out of the chaos – mapping the seasons to cultivate fields, studying pendulums to build clocks and reproducing proteins to form vaccines. Despite our structured ordering of the world, nature insists on reminding us of its randomness.

“Randomness is not exactly the same thing as uncertainty, but it’s closely related,” says Lightman. “The most well-known example of the benefit of randomness is the mutation of genes. Spins of the genetic roulette wheel aren’t planned, and their outcomes aren’t known in advance, but without them biology would be stuck with a small number of inflexible designs – there would be less biodiversity and many organisms would die out, unable to adapt to changing their environmental conditions.

Uncertainty in Art

Despite his training as a scientist, Lightman discussed the characteristics of literature and music alongside the fundamentals of quantum mechanics. The art that humans produce to make sense of the world is essential to understanding uncertainty.

Brianne Bilsky, Ph.D., Dean of Berkeley College and a Lecturer in the English Department at Yale University, has spent her career researching and teaching broadly, on topics including literature and war; rhetoric and composition; and media and information. The works that she asks her students to analyze are often ripe with ambiguity.

“Many World War I soldier-poets, such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, packaged the horrors of war in highly-structured poetic forms,” Bilsky says. “The resulting dissonance underscores the devastating effects for readers, both then and now, who were not actually on the front lines to observe them firsthand.”

Bilsky also teaches the metafictional novel A Tale for the Time Being, a 2013 Booker Prize Finalist, which was written by Ruth Ozeki, another panelist. Ozeki is an award-winning novelist, filmmaker and Zen Buddhist priest, who teaches creative writing at Smith College. Her novels weave together modern topics, such as science, religion and environmental politics into the narrative form.

Ozeki approaches uncertainty as both an artist and a Buddhist. As an artist, Ozeki spent the vast majority of her life without a “proper job,” which led to constantly occupying several roles, wearing numerous hats and living a life apart from the routine of a 9-5 office job.

“As a novelist and a filmmaker, I’ve lived most of my life this way kind of lurching from one uncertainty to the next, well, because that’s what artists do,” Ozeki reflects. “Certainty comes with certain strings attached, which can be very difficult and challenging for an artist.”

As a Buddhist, Ozeki advocates a very blunt understanding of uncertainty – the only thing anyone knows for certain is that they will die. The circumstances of death and the circumstances of life are uncertain. Living in that place of uncertainty, therefore, is the essence of being human.

“Uncertainty is the human condition and one of the root causes of human suffering,” Ozeki argues. “We want to be certain, we want to know and in the absence of that knowing we suffer.”

Uncertainty in the Humanities

While the panelists approached uncertainty from different starting points, there was a clear overlap in their interpretations and insights. Bilsky, for example, discussed being drawn to postmodern literature, where the plot defies simple summary and even the narrators are unreliable, in her academic career. Kahneman brought up an intriguing dichotomy of human life: that individuals both abhor uncertainty and seek out novels and scenarios imbued with ambiguity.

Integral to all the examinations of uncertainty on display is the value of an interdisciplinary approach. Ozeki examined the process of creating art alongside the practice of religion. Inherent to the humanities is a dedication to using multiple tools and resources from varying fields to answer big questions.

“It’s my hope that, with a little luck and a lot of hard work, students will come to see that if we take an interdisciplinary approach from time to time we just might become a little more certain about the value of uncertainty,” Bilsky says.

The humanities are uniquely equipped to tackle big questions without discrete answers, according to Pireddu.

“Uncertainty propels the acquisition of knowledge,” reflected Pireddu. “Ironically, it is often also the outcome.”

-by Hayden Frye (C’17)