Which Witch: Two Professors Use Historical Research to Teach Class on Different Forms of Witchcraft from Around the World

Alison Games, Ph.D. and Dorothy M. Brown Distinguished Professor of History, and Amy Leonard, Ph.D., professor of History and director of undergraduate studies, co-instruct the course Witches and Witchcraft in the Early Modern World. The two professors developed and teach this class because the “study of witchcraft is an entry point into everything that makes us human.”

“When we are talking about witches and witchcraft, we are really talking about the ideas people have about good and evil, about how they think society, family, and community should function, about their relationship to deities, and about their deepest fears,” says Games. “It’s also a subject about which there are wild misconceptions – assumptions about how many, who, when and where are all called into question that in turn demonstrates the importance of historical analysis.”

Which Witch is a Witch?

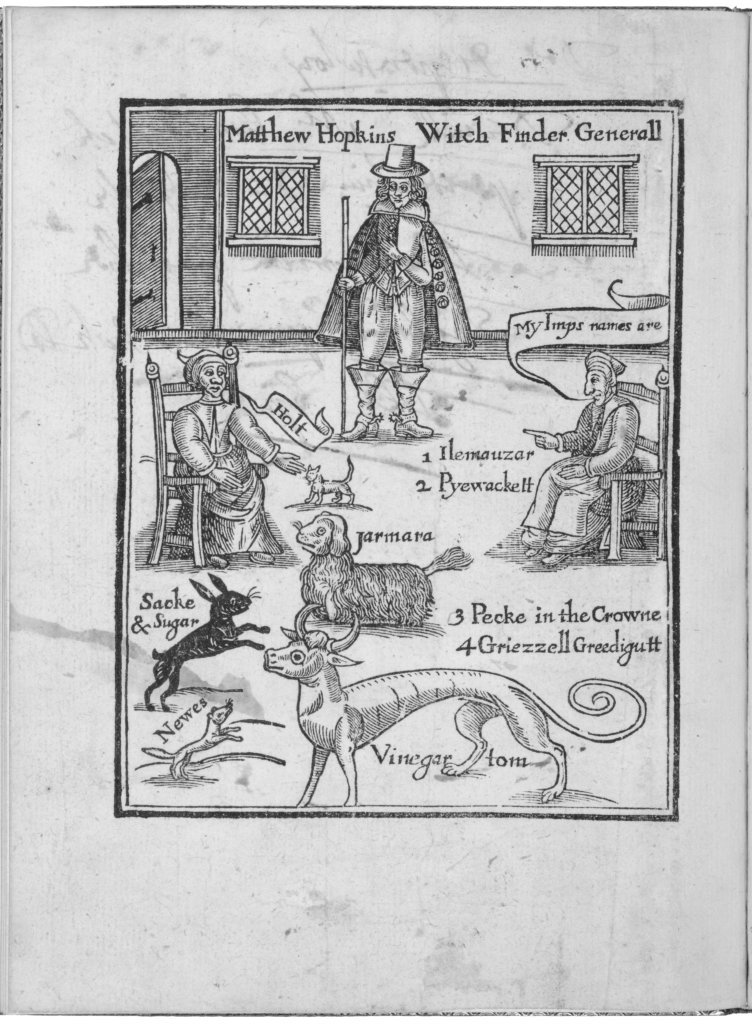

English witches calling to their familiars. Source: Matthew Hopkins, The discovery of witches (London, 1647). Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Witches and Witchcraft is a history department seminar, offered as an upper-level class until 2020, when Games and Leonard transformed it into a first-year seminar. The course asks the question “what is a witch?” through a wide-ranging exploration of the phenomenon of witchcraft in Europe, Africa and the Americas over the course of several centuries.

The two professors use this approach because the assumption of nonspecialists around witchcraft tends to focus on two places: Germany and Salem.

These two places had both shared Christian beliefs and common targets of witchcraft accusations–especially European women–but looking just at these locales misrepresents the incredible variety of witchcraft beliefs, not only within Europe itself, but also in the Americas and Africa. The tensions and conflicts in these diverse beliefs became especially apparent once Europeans, Africans, and Americans met in colonial, diplomatic, military and commercial contexts.

In their course, Games and Leonard show how widespread and diverse the ideas of witchcraft were by talking about places like Iceland, the kingdom of Kongo and colonial New Spain that go beyond what students might traditionally think of when they think of witchcraft.

“We try to move away from the many shared assumptions about witchcraft, and to introduce our students to a wide array of societies where witch beliefs were widespread,” explains Leonard. “While different societies had distinct ideas about witchcraft, especially those Christian societies that came to associate witchcraft with the devil, ideas about specialized practitioners able to perform healing or harmful magic with supernatural aid were common.”

Since these ideas were so pervasive, the professors chose to center the course around the collisions that ensued as people from Europe encountered those unlike themselves in places like Africa and the Americas and consider how individuals made sense of strangers in terms of their ideas about witches.

For example, Jesuits in territory Europeans called New France (modern-day Canada) wrote about what they thought were the diabolical practices of indigenous people–but those same indigenous people worried that the Jesuits were witches, and likely executed at least one, Father Jogues, as a suspected witch.

“One of the advantages of looking at these practices beyond Europe, and especially in colonized regions, is that one starts to see a much more extensive cast of characters as likely witches — Jesuits, Africans, indigenous people of all sorts and, as was often the case, European women,” Games says. “The chronology shifts, too, with Europeans in the Americas continuing to worry about witchcraft and prosecute and punish offenders in the form of alleged poisonings by enslaved practitioners, for example, long after Europeans in Europe had lost interest in prosecuting witchcraft as a crime. In colonial settings, these different beliefs converged and conflicted in the context of asymmetrical power dynamics.”

To teach this course, Games and Leonard pull from a large arrangement of sources including trial records, legal, religious and medical treatises, plays, broadsides, music, works of art, woodcuts and an astonishing assemblage of material objects like witch bottles and bundles, items used in divination, or implements of torture.

This rich archive exists both because the illegality of witchcraft at the time generated so many legal documents and also because witchcraft beliefs were so pervasive that they intruded in all aspects of life. This remarkable archive allows modern-day researchers to fully immerse themselves in a remote place in the past.

“These cases introduce readers to family and community life in immediate and intimate ways,” says Leonard.

A Commitment to the Craft

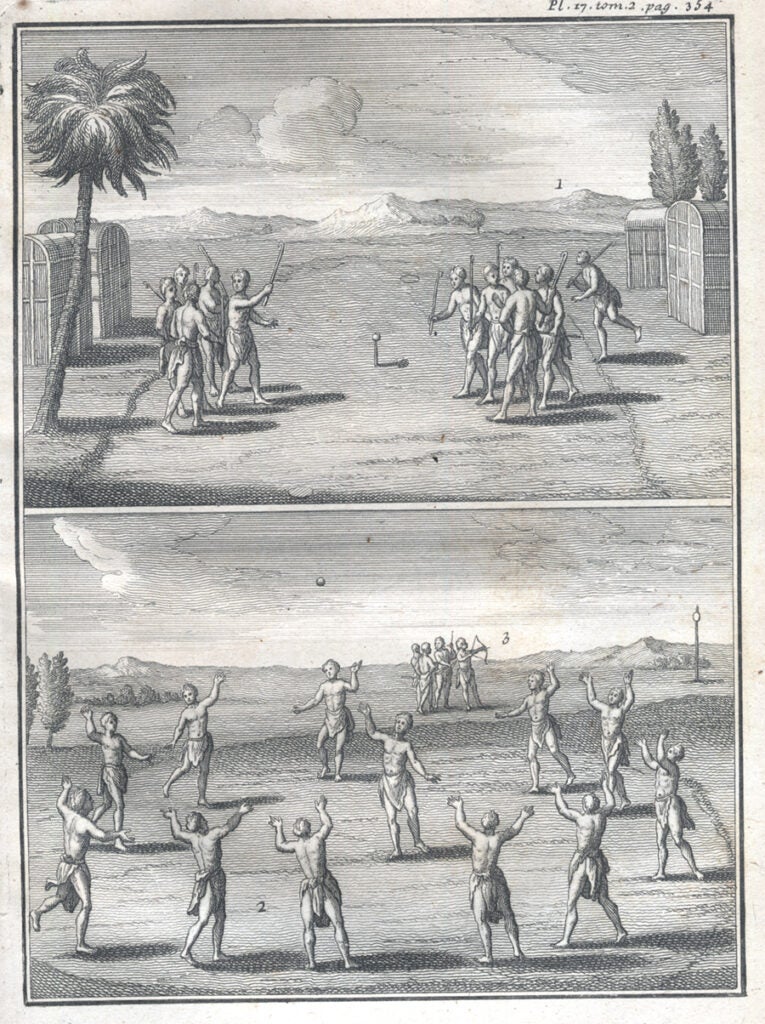

Top: An Iroquois lacrosse game, which the Jesuits understood as a practice organized by a “sorcerer” to help people heal from an epidemic. Source: An Iroquois lacrosse game. Bottom: A depiction of an Iroquois healing ritual. From Joseph-François Lafitau, Moeurs des sauvages ameriquains (Paris, 1724). Courtesy of Georgetown University Library Special Collections.

Both Games and Leonard began teaching the history of witchcraft as part of their broader research interests. Games is a historian of early America and the Atlantic world, while Leonard specializes in gender in early modern Europe.

Games published Witchcraft in Early North America (2010), which came directly out of their experience teaching the class and from thinking about complex beliefs about witchcraft as a way to analyze and understand multiple facets of the collisions that accompanied European incursions into foreign lands.

“The book also shows how ideas about witchcraft both persisted and changed in the circumstances of colonial encounters, and how Europeans absorbed some African and indigenous ideas and even came to rely on African and indigenous practitioners,” says Games.

Leonard explains that gender is at the center of her work, which is at the heart of any analysis on witchcraft. More specifically, her research examines the complex intersections between religion, culture and gender in early modern Germany. Her expertise in the history of nuns, celibacy and sexuality, both as lived experiences and as ideology, directly engages the beliefs and practices that animated witchcraft accusations and persecutions and helps us understand more fully how women were central to these tumultuous proceedings.