In ‘Gardens of Hope,’ Yuki Kato Shows How Urban Gardens Grow Community and Change

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina, conversations about recovery in New Orleans often focus on infrastructure, housing or tourism. But in the decade after the storm, another kind of rebuilding quietly took root across the city: urban gardens and small-scale farms cultivated by residents who wanted to nourish their communities and imagine a different future.

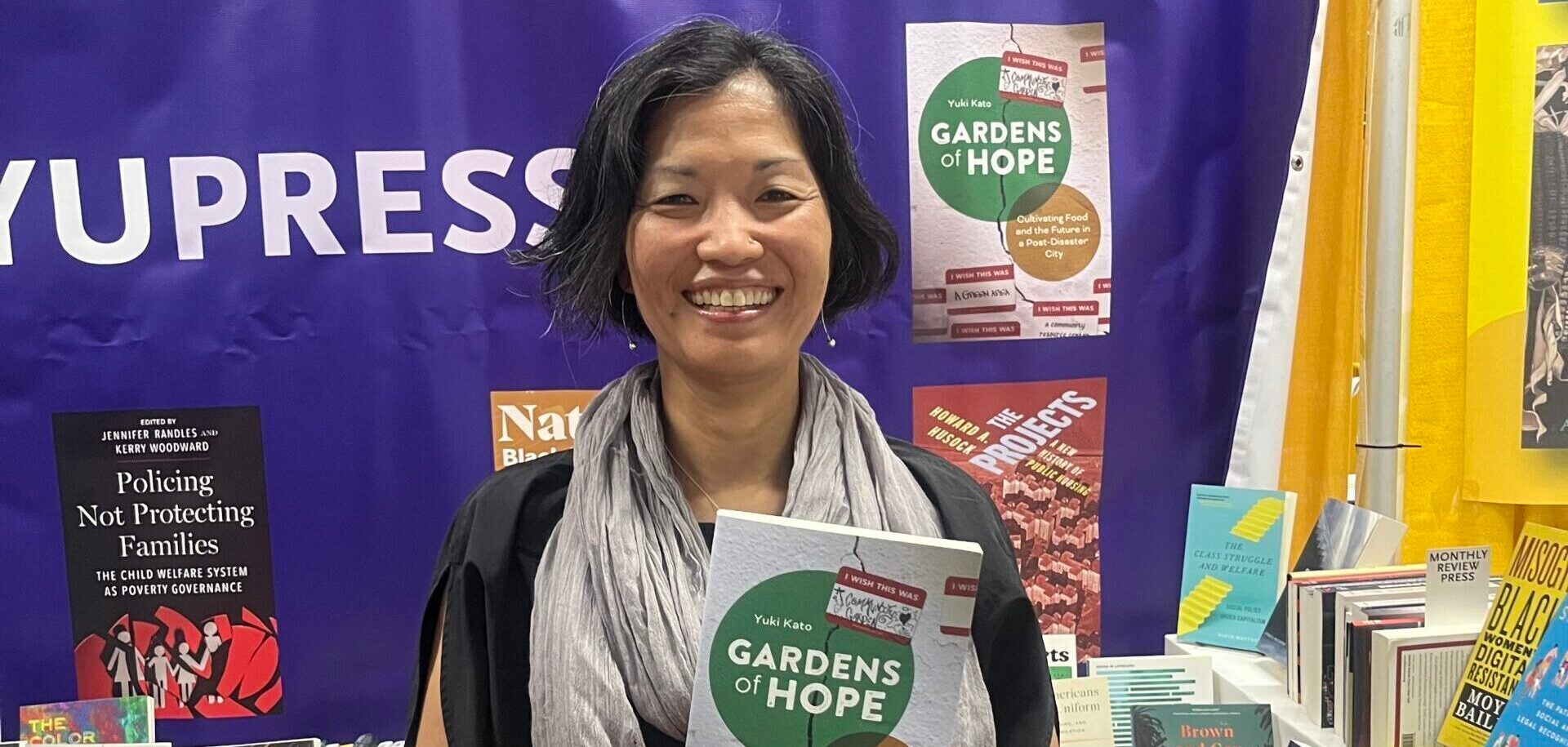

This movement, and the people behind it, are the focus of Yuki Kato’s new book, Gardens of Hope: Cultivating Food and the Future in a Post-Disaster City.

Kato, an associate professor in the Department of Sociology, recalls noticing gardens appearing across neighborhoods still devastated by flooding.

“I really started to notice that more and more gardens were starting every month or every year,” she said. “And so really, that’s how I got myself interested in, why are they doing this? What is this for? And what is it like to start and operate this kind of relatively larger scale food production in a city that’s still undergoing some major post-disaster recovery redevelopment.”

‘We Can Be the Change’

Kato’s book follows roughly 50 growers in New Orleans who, between 2005 and 2015, turned empty lots and blighted land into spaces of cultivation. Yet these individuals did not see themselves as activists. When Kato asked whether they identified that way, “not one of them said yes,” she said. They wanted change, but they wanted to enact it directly rather than organize around it.

To explain this approach, Kato introduces the concept of prefigurative urbanism — the idea of building the world you want to live in before that world exists, but as individuals rather than as a collective. As trust in government, corporations, and even nonprofits decline, communities increasingly turn toward self-determined action, Kato said.

In Gardens of Hope, published in May 2025, Yuki Kato follows roughly 50 growers in New Orleans who, between 2005 and 2015, turned empty lots and blighted land into spaces of cultivation.

In drawing similarities between prefigurative urbanism and prefigurative politics — a social movement tactic of manifesting the alternative world through direct action — Kato referenced the Black Panther Party’s breakfast program.

“So instead of petitioning the local school board, or to wait for the local government or even the federal government to implement some program to feed them, they decided to go ahead and feed themselves,” she said. “We also don’t have to wait for these larger changes to happen to receive the benefit of these changes. We can be the change.”

The immediacy of prefigurative urbanism allowed growers to demonstrate what was possible. But it also revealed limits. Because gardens were often maintained by individuals rather than collectives, many struggled to last. Some farmers lost access to land; others no longer had the capacity to keep the work going. The result was a pattern of powerful beginnings, followed by uncertain futures.

Access and Innovation

Structural inequities also shaped who could participate. Starting and sustaining a garden requires time, money, social networks and, in some cases, a comfort with bending legal norms.

“To be able to start something that’s out of the existing structure requires you to essentially fund yourself,” Kato said. “There is privilege in who gets to break the rules without fearing consequences.”

Kato encourages readers to reconsider what counts as innovation.

“So much of the concept of innovation has been packaged as something that happens in Silicon Valley,” she said. “But historically, marginalized people had to be innovative because the system excluded them.”

In New Orleans, Black residents and immigrants have long grown food and fished out of necessity and also to preserve their ancestral cultural heritage.

“But we were not calling that farm-to-table,” Kato said. “We were not calling that alternative food movement. It’s important to recognize that what we have come to call urban agriculture is not new.”

Civic Imagination

Yuki Kato is an urban sociologist whose research interests intersect the subfields of social stratification, food and environment justice, culture and consumption and symbolic interaction.

Some participants told Kato that reading the book offered “a good closure … a process for them to make sense of what they went through themselves over the course of the 10 to 15 years.”

This reflection became central to the project.

“I wanted to recognize my own growth as a researcher,” Kato said. “I had probably very little understanding of food justice and environmental justice … and I really taught myself that while I was writing this book.”

She emphasized that neither she nor the growers were the same people they had been when the work began: “We’re all learning and we’re not really a static person.”

Building on that reflection, Kato is continuing her work through a new research-based course next semester.

“This new project will focus on the gardens and farms in DC that no longer exist,” she said. Students enrolled in the course will be involved in data collection and analysis processes to gain first-hand experience in conducting research.

“We’re going to interview people who lost access or have left the urban agriculture projects for various reasons, in order to understand why some gardens fail to sustain for a long term and what these losses mean to the individuals involved,” Kato said.

The study adds critical examination of when well-intended projects fail or terminate unexpectedly.

As New Orleans marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Gardens of Hope asks readers to reconsider what rebuilding looks like, who gets to imagine change and what forms of labor and care are often overlooked.

Urban gardening, in this telling, is not a hobby — it is a form of civic imagination practiced with hands in the soil. These gardens did not simply grow food. They dared to grow alternative futures — unfinished, imperfect and deeply human.