Paradise Found: Book Recommendations with Daniel Shore

Milton scholar, promiscuous reader and chair of the English department Daniel Shore shares selections from his shelves for all occasions.

Read Professor Shore’s Recommendations

Historian Mireya Loza gathers and shares the stories of the immigrant and migrant farmworkers of the past and today — providing a clearer picture of the people who have fed and continue to feed us.

“¡Yo le digo!”

This was the response of Gustavo Eloy Reyes Rodriguez. On July 1, 2008, Professor of History Mireya Loza interviewed him about his experience as a bracero, one of 4.5 million Mexican guest workers who came to the United States from 1942 to 1964, as part of the largest foreign worker program ever sponsored by the U.S. government.

They were talking in his home in Oaxaca, Mexico, and she had just asked him if there were any gay men among the Bracero Program.

Sure, he responded.

Then: I will tell you.

Loza listened. Over the course of six years working with the National Museum of American History’s Bracero History Project, Loza has listened to Rodriguez and more than 90 people tell their stories as well as trained faculty and staff who helped amass over 800 oral histories for the project’s online archive.

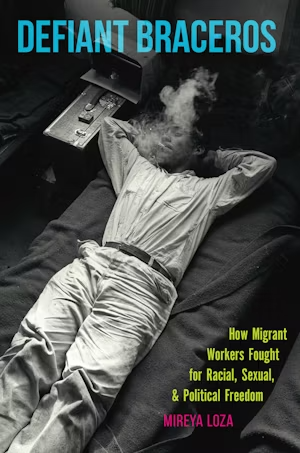

This work would become the focus of her research, her book Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual and Political Freedom, a traveling exhibition for the Smithsonian Institution, and the research she teaches Hoyas to conduct. And it all began with an undergraduate assignment.

Mireya Loza’s expansive work, Defiant Braceros.

“As an undergraduate, I was part of the first cohort at my university to take classes in Latino studies and ethnic studies, which were pushing the envelope in terms of being recognized as a valid body of scholarship,” remembers Loza. “In one of my first classes, the professor asked us to find our oldest family or community member and conduct an oral history.”

Oral histories, which rely on personal interviews to understand historical events at the individual level, are an essential tool for students of the humanities — shedding light on details and perspectives left out of other forms of historical narratives.

“Equipped with my little cassette player, I conducted my first oral history with my uncle, who had worked in the Bracero Program,” said Loza. “I realized that I loved talking to people, interviewing them and asking questions about the ways in which power shapes their lives. I was able, because of the classes that I had taken, to know how to do that — to fill in the pieces with the literature.”

As a graduate student at Brown University, Loza began working with the National Museum of American History, which was carrying out a massive transnational project to collect oral histories in both Mexico and the United States.

“For the National Museum of American History, this was a novel concept — that you could collect stories of U.S. history outside of America,” said Loza. “These people, whose lives across a political boundary, also hold part of that American story and without them it is incomplete.”

Loza traveled across the United States to help run various collecting sites, which served as loci for identifying and interviewing braceros and their families. The program relied on a town hall model which brought together nonprofits, local organizations and other partners to cultivate a community of people who had lived through or observed the Bracero Program in action.

“We interviewed everyone we could — not just braceros, but children, wives and neighbors,” said Loza. “Together, we built one of the largest thematic repositories of LatinX history. ”

Published in 2016, Defiant Braceros won both the Theodore Saloutos Book Prize, which is awarded by the Immigration and Ethnic History Society, and the Smithsonian’s Secretary’s Research Prize. Loza’s research helped build a wider understanding of the Bracero Program and contributed to a settlement program, initiated by the Mexican government, which provided former braceros with compensation for their wages that had been garnished during the 1940s.

By pulling at a single thread of interest discovered in an undergraduate classroom, Loza dove deep into research that not only provided her with accolades but helped shape the academic and public discourse on a topic that personally affected her, her family and millions of others.

Mireya Loza works with a graduate student at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History examining her uncle’s bracero contract. Photo by Rudy Mondragon.

On the Hilltop, Loza seeks to ignite the same curiosity for her students.

“I bring the real world into my classroom so that students can get a sense that the humanities are a vibrant place where they can tackle current problems, learn real skills and find a pathway to employment,” said Loza. “I always have to remind my students that it’s not about the discipline in the humanities that you pick, but the critical thinking that the humanities teach that can be applied across a multitude of careers and sectors.”

As an undergraduate, Loza remembers her family pestering her over pursuing a different field, what she calls popular telenovela careers — doctor, engineer and architect. While valid areas of interest, they weren’t for her and the humanities opened up doors that she didn’t even realize existed.

“Exploring the humanities taught me critical reading and writing skills, it taught me how to think about the wider world around me, about material inequality and ways in which we build discourses around the topics I was interested in,” said Loza. “Studying the humanities set me on this path to ask questions, to think about my family’s history, their community’s history and to make connections with that history and the present.”

At Georgetown, Loza has mentored many exceptional Hoyas, including Grace Elicker (C’22), an American Studies major who first met Loza in a course exploring workers in the American food system. Elicker, who was recently accepted into the doctoral program in Columbia University’s Department of History with a full-ride, credits Loza with expanding her perspective on what labor history can encapsulate.

“Before that course, my idea of food production was bound to the binary between the people who grow food and those who eat it, and after that I had a more nuanced understanding of how many hands are involved in the food production process, and the struggles these workers face in this system,” said Elicker. “That first class forced me to reckon with the narrative in which workers are saturated in the American labor movement, and how they are disinherited from that story.”

After taking that first course with Loza, Elicker went on to become her research assistant, and has since helped develop an ongoing digital humanities project documenting the first Mexican guestworker program during World War I.

“Grace is rendering prototypes for this mapping,” explained Loza. “This not only allows us to see the photographs of the actual workers, but apply a second layer of data analysis on top of that information.”

The project aims to identify the workers who participated in the program and aggregate as much information about them as possible. To build out this data source, the team is working with worker cards that were issued at the border by the Department of Labor.

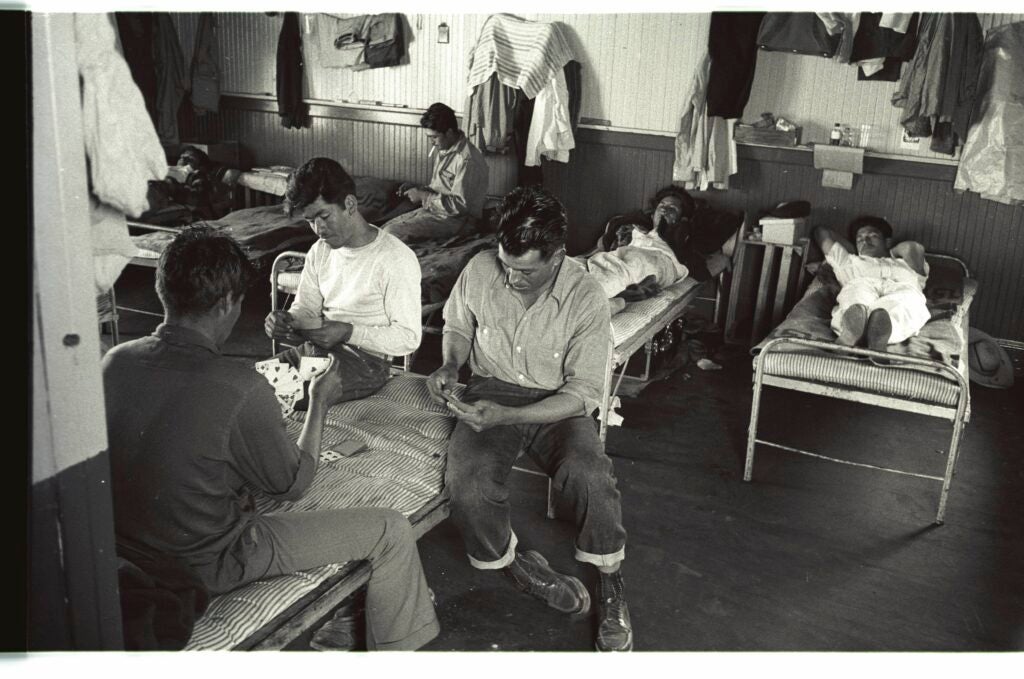

Braceros sit on a bed and play cards in a living quarter at a camp in California, 1956. Photo by Leonard Nadel, courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

“We aim to visually represent the data gleaned from these ID cards by creating a map that traces migration patterns from an individual’s last residence in Mexico, to their point of entry into the United States and their final destination within the United States,” said Elicker.

To date, the project has digitized some 500 migrant worker cards, but for Elicker that’s just the beginning.

“The cards only tell a fraction of each worker’s story because there is still so much that remains unknown: where they were born, where they went after the program and, most importantly, their experience in the program,” said Elicker.

For Elicker, this research not only enriched her undergraduate experience, but has allowed her to continue preserving history since graduation.

“Throughout the project, I have learned how digital humanities can serve historical projects,” said Elicker. “Through the visual representation of the map, we can offer both a human portrait of a real person who came to the United States to work over a hundred years ago, and document large-scale migratory patterns from a statistically significant gathering of data.”

Since publishing Defiant Braceros, Loza has worn many more hats beyond that of professor and historian — working as both a museum curator and a policy expert. Last year, Loza was tapped by the Biden administration to participate in the first USDA Equity Commission.

“We are trying to think about what the USDA has done to increase equality between Black farmers and nonblack farmers, but also amongst farmworkers and farmers,” explains Loza. “Trying to undo a lot of the historic policies that set up these inequalities is a huge challenge, but also very novel as a historian because I’ve always been asked to talk about the past and I’ve never been invited to be at the table when people are crafting contemporary policy.”

Mireya Loza being interviewed during the opening of De Últimate Hora.

Loza continues to curate exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where she recently worked on the exhibit De Últimate Hora: Latinas Report Breaking News, which opened late last year.

Her next book project, tentatively titled The Strangeness and Bitterness of Plenty: Making Food and Seeing Race in the Agricultural West, focuses on the intersection of immigrant labor and the construction and maintenance of the agricultural system in America. She is particularly interested in the distinction between farmers and farmworkers in the United States.

“I’m thinking about how some of the people who do the hardest work to feed us every day are also the most marginalized in our society,” said Loza. “We have separated farmers from farmworkers not based on labor or expertise, but because of ownership. I’m trying to pull that thread back as far as I can to better understand how we got here and how we might build a more just food system.”

Throughout her work in the classroom and outside of it, Loza seeks to listen and amplify the voices, experiences, and lives of others.

“I love public history and the public humanities — a call to bring the humanities to the public, to make sure that we’re addressing their concerns, producing projects that are relevant, answering pressing questions that solve problems, that build knowledge,” said Loza. “I love it. To me, it’s humanities for the people.”

Milton scholar, promiscuous reader and chair of the English department Daniel Shore shares selections from his shelves for all occasions.

Read Professor Shore’s Recommendations

Whether in the farthest reaches of our solar system, her lab on the Hilltop or her New York Times bestselling book, Professor Sarah Johnson seeks out signs of life — and connection.

Read Professor Johnson’s Story