The Untold Story of the Windy City: Georgetown Professor Paints New History of Mexican Americans in Chicago

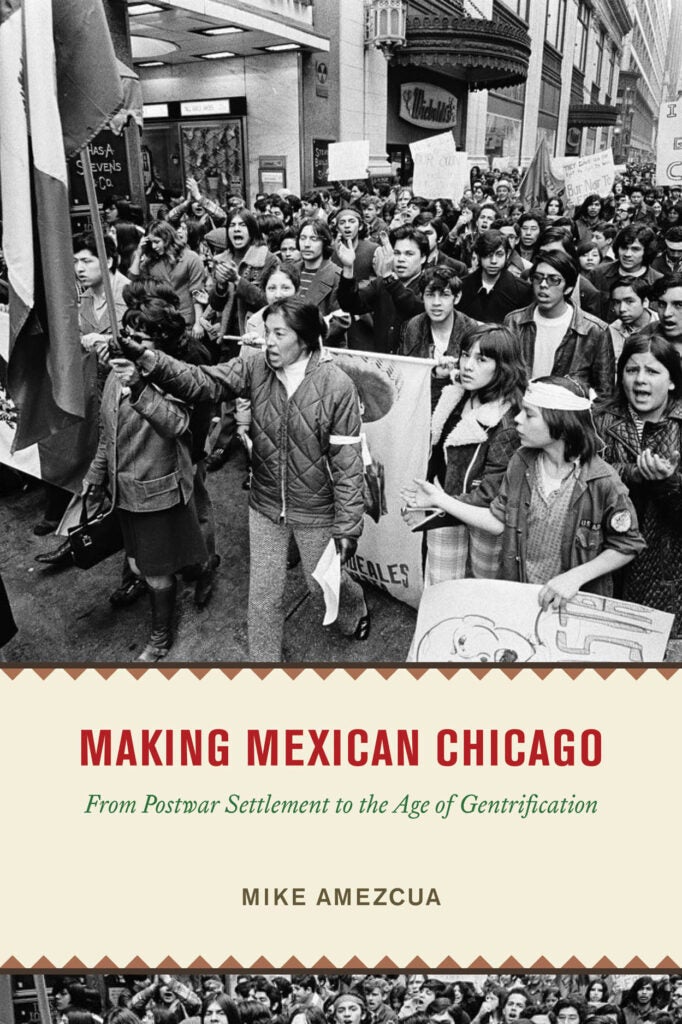

Cities are designed, funded and constructed by architects, financiers and bricklayers. Their identity, however, is imbued by the communities and people who call them home. Mike Amezcua’s new book, Making Mexican Chicago, tells the story of the Windy City as it was built by its Mexican and Mexican-American population, exploring the ways in which post-WWII federal policies, funding and priorities shaped the reality of urban lives in the second half of the 20th century.

Amezcua, an assistant professor in the Department of History, launched the book by hosting a conversation alongside fellow urban historians, including Marcia Chatelain, a professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown. They were joined by Davarian L. Baldwin, the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of American Studies at Trinity College, and Natalia Molina, a Distinguished Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California.

Fighting for Identity

While Chicago’s history is typically understood as both multiracial and multicultural, Mexican Americans have been left out of the picture despite Cook County being home to the third-largest Mexican-American population in the country. For Amezcua, understanding how that community shaped Chicago is essential to understanding the city.

“The book highlights the struggle to make a sanctuary out of Chicago,” Amezcua says. “In fighting for space, housing and resources, Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans remade the city one neighborhood at a time.”

Amezcua’s analysis of Chicago covers broad historical trends, including the interplay between federal, state and municipal forces. From the Immigration and Naturalization Service deporting Mexicans and Mexican Americans through Operation Wetback, to the displacement of families through the urban renewal movement, Amezcua confronts the messy history of deportation and demolition efforts undertaken by state actors with clear eyes.

“I wanted to look at stuff at a micro level,” says Amezcua. “To look at the ways that streets become boundaries, streets become borders and, eventually, battlegrounds, and in this way we can understand the larger power structures of the city and the state.”

Bringing Communities to Life

Telling the devastating story of the state-sponsored assault on Chicago’s Mexican-American population doesn’t prevent Amezcua from illustrating the intimacies and joys inherent in the lives led by that same community. Amezcua pays special attention to how Mexican Americans became involved with their communities, through politics, churches and schools.

“I never got to see Latinx Chicago before your book,” says fellow urban and Latinx historian Molina. “You see Mexicans as real estate brokers, club women, protestors, beauty queens, property managers, youth working for change. You see them in different spaces – neighborhoods, political clubs, pageants, parades, Fiestas Patrias, ballrooms, public housing, city hall, in machine politics and churches. They celebrate, they struggle, they buy property, they are deported, they are targeted by the INS, they vote — they build Chicago.”

By illustrating the broad strokes of Chicago’s urban history with the realities and details of every life, Amezcua tells a unique, fully-formed and imminently readable history of Mexican-American communities. His writing informs and broadens our history of how urban landscapes and urban lives were transformed throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. It’s essential reading for anyone interested in American history, Chicago or the Mexican-American experience.

Published by the University of Chicago Press, Making Mexican Chicago is available now.